Texts by Patrick Carpentier, Marcel Dugas and Robert Duval. English translation by Philippe Cousineau.

Cliquez ici pour consulter une version française de cette page.

Montreal was privileged to witness two prominent baseball players who would go on to play a major role in the fight for civil rights in the United States. Jackie Robinson was the first African-American player to break Organized Baseball’s color line in the 20th Century. Roberto Clemente was the first Latin American player to be inducted in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. These two heroes were committed to the fight for civil rights alongside Reverend Martin Luther King and were instrumental in advancing the status of minority players throughout baseball. And both started their professional career with the Montreal Royals.

Montreal was a booming city following World War II. The province of Quebec’s largest city was entering a period of economic and cultural growth. While it was predominantly French-speaking, it also hosted a large English-speaking population, and many ethnic communities originating from different parts of Europe. There was also a black community made up of immigrants from the United States and the Caribbean that had made the city one of the hotbeds of jazz music in North America starting in the 1920s. Montreal’s cultural scene was dynamic, and so was its sports scene. At the time, baseball was the favorite summer sport of Montrealers.

A first edition of the Royals played from 1897 to 1917. They then made a triumphant return in 1928. Playing at Delorimier Stadium, the most modern ballpark in minor league baseball, the Royals had quickly become a prized attraction for Montreal fans. They won a first championship in 1935 thanks to the offensive prowess of Quebec-born player Gus Dugas. In 1939, the Brooklyn Dodgers made them their top minor league affiliate. Many future major league stars came through Montreal over the years. It is in this context that Jackie Robinson and Roberto Clemente arrived in the city.

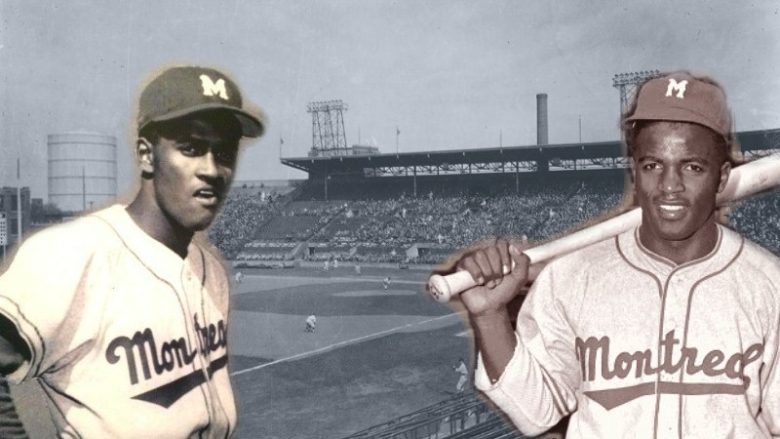

Jackie Robinson (1919-1972)

Known mainly as the man who broke the rigid system of racial segregation that was prevalent in baseball, Jackie Robinson had a profound impact on 20th Century American society. His role as a pioneer in sports, media and the business world, and a life spent fighting for a more just world brought him numerous honours, including having his uniform number 42 retired throughout professional baseball. A central chapter of Jackie Robinson’s life story was written in Montreal, and Quebeckers were not simply spectators, but active participants in what was called the “Great Experiment” of the integration of sports.

An exceptional athlete from his youngest days, he was a sports star in college. He excelled in all sports – except in baseball. If there had been more professional opportunities for African-Americans in basketball or football at the time Robinson signed on to join the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League, the course of history could have been completely different.

In the fall of 1945, Robinson became the first African-American in the 20th Century to sign a contract with a major league organization, namely the Brooklyn Dodgers. But before he could play in the big leagues, he had to learn his trade with the Dodgers’ main farm team, the Montreal Royals.

In spite of the huge pressure placed upon him and of the hostility he encountered from rival players and fans in certain cities, Jackie proved beyond all doubt that African-Americans belonged in “organized baseball”. He was the main offensive weapon of a team that won the regular season championship by 18 ½ games, leading the league in batting average, hits, and on-base percentage.

After winning the International League pennant, the Royals also won the Junior World Series, which were the championship for all minor leagues. At the end of the final game, Montreal fans, who had supported Jackie without fail from the season’s first day, did not want to let their new hero leave. They chanted his name, held him aloft, and even chased him down the street, “not out of hate but because of love”, as a journalist who witnessed the scene described it.

The following spring, Jackie began a ten-season career in the major leagues that led him to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. His career statistics are very impressive: Rookie of the Year in 1947; MVP in 1949; a .311 batting average and an OPS of .883 with a WAR of 61.4, and almost two and half times as many walks as strikeouts.

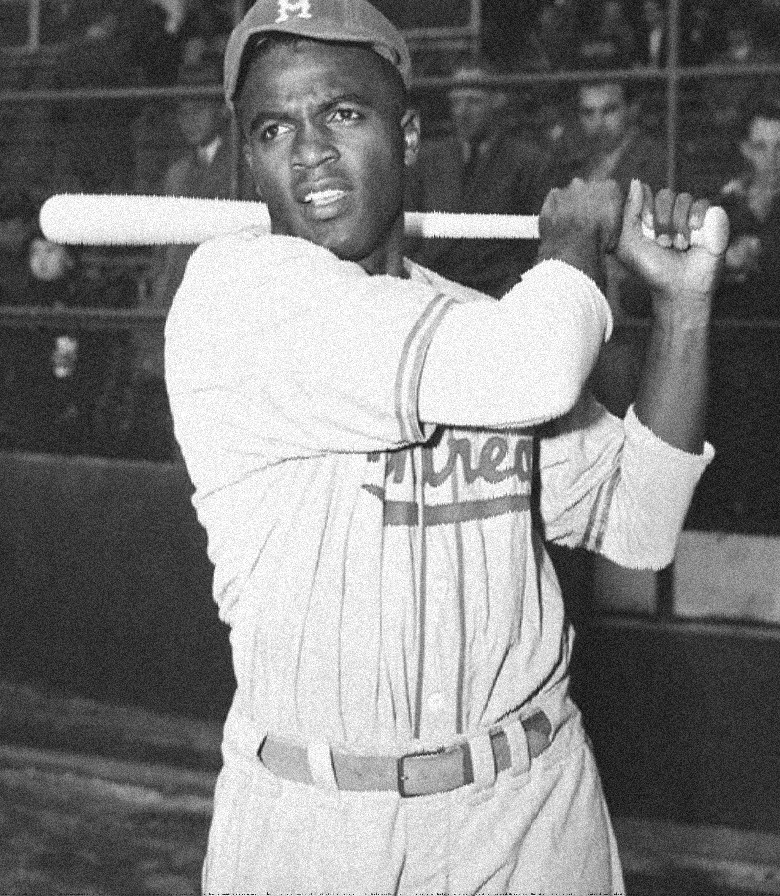

Roberto Clemente (1934-1972)

While Jackie Robinson started his career in white organized baseball with a lot of fanfare when he played in Montreal in 1946, Clemente did so in the same place eight years later, but much more quietly. However, his career in professional baseball was a long one and was highlighted by numerous feats. From 1955 to 1972, with the Pittsburgh Pirates, he won two World Series, and received, among other honours, twelve Gold Gloves, four National League batting titles, one regular season Most Valuable Player Award and another one for his play in the 1971 World Series when he was already 37. The Porto Rican star ended his career with exactly 3,000 hits and was inducted in the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility in 1973, following his death in a plane crash on December 31, 1972, when he was on a mission to deliver relief supplies to Nicaragua following an earthquake there a week earlier.

Born in the small town of Carolina, Clemente signed his first contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers on February 19, 1954, when he was only 19, for a salary of $5,000 and a signing bonus of $10,000. The Dodgers loved with his speed, his arm and his aggressiveness. However, the rules of the day forced a team that signed a player for a combined salary and bonus over $4,000 to keep him in the major leagues for two years, or risk losing him in the minor league draft. It is therefore quite a surprise that Clemente spent the entire 1954 season in Montreal with the Royals, while playing relatively little. Some people have claimed that this was in order to hide him, to prevent him from being drafted away by another team, but others have stated that manager Max Macon simply considered that he was not ready for AAA baseball, as he would swing at just about any pitch. Macon would use Clemente mainly against lefthanded pitchers in the season’s second half, or as a defensive substitute. Clemente was deeply unhappy about riding the bench and thought a number of times about leaving the team. As teams were only allowed to lose one player each in the draft of so-called “bonus babies”, the Dodgers attempted to reach a deal with the Pirates, who held the first pick, so that they would select someone other than Clemente, but Branch Rickey wanted Clemente and no one else.

For a long time while he was playing, Clemente was not appreciated as much as he should. This was largely because he was playing in a small market, he was often injured, and he did not have great relations with the media. He was a man proud of his race who did not accept being treated like a second-tier star. Moreover, while people saw his as Latino, he was also a black man and, although to a lesser extent than Robinson, was the object of racial discrimination especially in cities in the southern United States. In certain places, he could not stay in the same hotel or eat in the same restaurants as his teammates. That being said, everyone who ever saw Roberto play remember him as an extraordinary athlete, very aggressive on the field with an arm that has hardly ever been matched.

During the 1971 season, when the Pirates were the visitors at Jarry Park, there was a long rain delay and Expos organist Fernand Lapierre was just about the last man left in the ballpark, playing tunes while spectators sought shelter under the stands. Clemente asked who the organist was and climbed up in his uniform to meet him, along with teammate Jose Pagan. The two asked him to play some Latin American songs and the three had a ball singing and dancing together. Clemente and Lapierre became good friends, the former becoming in effect the latter’s mentor. If Roberto had not tragically died, Lapierre was supposed to pay him a visit in his homeland in January 1973, with Clemente footing the bill.

For Porto Ricans, Roberto is a national hero. Every winter, he returned home to play baseball and to ensure the sport continued to flourish. He fought against injustice his entire life and died trying to help the people of Nicaragua. Roberto Clemente was a great star on the field, but also an underappreciated hero.